|

| DAC does Henry III |

Today might be the feast of St Valentine but, on this day in

1265, Henry III’s heart must have turned cold. Held prisoner by Simon de

Montfort, he stood humiliated in the chapter house of his beloved Westminster abbey while an announcement was made that he had sworn to subjugate himself to

Montfort’s council. At the same time it was proclaimed that Henry had vowed to

abide by Magna Carta. Whilst a royal promise to keep the Charter was nothing

new (the 1225 issue of Magna Carta had been confirmed by Henry in 1237 and

1253), circumstances in 1265 made this occasion very different. Henry’s oath

was not part of a mutual bargain between king and subjects, provided freely in

return for a grant of taxation. Instead, it was extracted from him by force.

Defeated on the field of battle at Lewes in May 1264, and held captive by the

triumphant Montfort, now de facto ruler of England, the king had no choice but

to endorse Magna Carta and the radical Montfortian constitution in the same

breath.

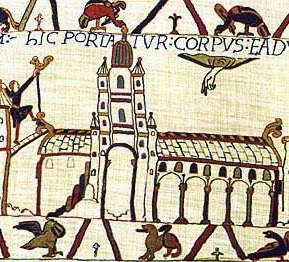

Henry’s situation was all the more demeaning because the

scene of his humiliation, Westminster abbey chapter house, was the very place

Henry had built to profess the majesty of his rule. He had begun the rebuilding

of Westminster abbey in 1245 (in honour of his patron saint, Edward the

Confessor) and had personally overseen the design of the chapter house.

Envisaging a venue where he would meet his nobles in parliament, the king had

commissioned a lectern decorated with wrought iron and, possibly, gilding. Henry

must have imagined himself making dignified speeches, stood on the magnificent

tiled floor that bore his coat of arms, bathed in light from the house’s vast

windows, surrounded by prelates and magnates who sat awed by his authority. Instead,

the king stood dumb (if, in fact, he was there at all) while a rebellious

subject announced on his behalf that the king was now subject to conciliar

rule.

The history of Magna Carta is bound up with that of

Westminster abbey. The old abbey had been a site for assemblies since the days

of its founder, Edward the Confessor, and it was there in St. Katherine’s

chapel that Magna Carta had been confirmed in 1237. The chapter house of the

new abbey was built by the first king to govern under the Charter’s

restrictions and was designed with the new modus vivendi for ruler and ruled in

mind. Even if the events of 14 February 1265 showed that this relationship had

been usurped by a more radical model, it was here in the chapter house that the

importance of Magna Carta in the language of good government was confirmed.

Henry’s confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265 is discussed in a Feature of the Month on the Magna Carta Project website. For more on Henry’s

chapter house, see: D. A.

Carpenter, ‘King Henry III and the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey’,

in R. Mortimer (ed.), Westminster Abbey Chapter House: The History, Art and Architecture of

'a Chapter House Beyond Compare' (London: Society of Antiquaries of London,

2010), 32-9