Clause 39 of Magna Carta 1215 is perhaps the most famous of

the Charter’s 60-odd clauses: ‘No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or

disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against

him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the

law of the land.’

Setting out the principle that the government should be

bound by the law – that the ruler could not simply attack his subjects as and

when he pleased – it has long been held up as a shield against arbitrary government

in those countries where the Charter’s principles have informed the

relationship between ruler and ruled.

|

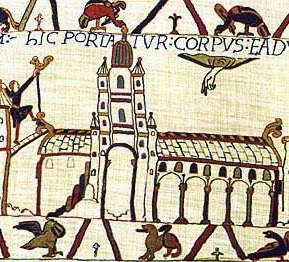

| Injustices committed under King John, as depicted by Matthew Paris |

But the reality of John’s rule was, in fact, more brutal

than even cases such as this would suggest. In preparing his commentary on clause 39 for the Magna Carta Project, Henry Summerson has undertaken a

thorough investigation of how John ruled on a day-to-day basis. The result is a

picture of a government that was systematically aggressive, violent and arbitrary.

The ability and willingness to provide justice to those who

sought it was, as far as the king was concerned, a tool for exercising his

power:

‘What mattered... was his ability to variously advance the men he trusted, fend off those he did not, and play upon the hopes and fears of both in such a way as enabled him to retain their loyalty, or at any rate frustrate their disloyalty.’

The king’s court might follow sound procedure and provide justice

to those who sought it, although not if it was the king himself who had inflicted an injustice upon one of his subjects – which was all too often the

case. But Angevin kingship was as much personal as it was

procedural. The king’s good will (benevolentia) and his ill will (malevolentia)

were fundamental to the operation of royal rule:

‘The world of the Angevin court and government was one of violent, almost black-and-white, antitheses, in which benevolence and malevolence were polar opposites, with little neutral ground between them – anybody who lost the one stood in immediate danger of incurring the other, and of seeing his affairs go to ruin in consequence, exposed to the caprices of an administration which was always heavy-handed and often downright violent as well.’

The effects of the king’s anger could be devastating. Henry

II and Richard I demanded vast sums of money from their greater subjects to buy

back the king’s good will, often for unspecified offences or in the pursuit of

their grudges. But King John pushed

these arbitrary methods of government much further.

One of John’s favoured tools was dissesin – the repossession

of a subject’s lands. This was a severe blow to the subject’s prestige and

social status but the financial consequences were also severe:

‘anyone disseised on the king’s orders faced the loss of all his or her movable assets... [and potentially] the complete devastation of the property. Thus in 1215 the houses on the land of Henry of Braybrooke were to be completely demolished, while a year later order was given that all the lands of William of Hastings were to be wasted, his demesnes destroyed and his castle pulled down.’

It was not only earls and barons who suffered at John’s hands:

‘What sets John’s kingship apart from that of his two predecessors is the number of lesser men who were similarly targeted... almost any offence, whether real or not, could result in dispossession, carried out on orders whose arbitrariness was if anything underlined by the frequency with which they were said either to have originated in the king’s malevolence’

Henry has uncovered a catalogue of examples that reveal how

‘disseisin had become a well-nigh automatic reaction on the part of the king

and his agents to any misdeed or suspicious act which came to their attention.’

Imprisonment and physical violence, and the threat thereof,

were also tools readily used by the king. When the kingdom was placed under an

interdict, in 1208, John

'encouraged, or at least countenanced, assaults on the clergy (the Barnwell Chronicle referred to clerks suffering through swords and gibbets), and then he forbade such attacks, with the hardly less intemperate declaration that if he could lay hands on anyone responsible, "we will have him hanged on the nearest oak".'

In 1215, John was able to capture Belvoir Castle 'by threatening to have

its lord (and his prisoner), William d’Aubigné, starved to death if his men did

not surrender.’

But the king’s threat of violence had also become a normal tool

of administration, threatened as punishment for relatively trivial offences

that merely inconvenienced the kings’ household:

‘In 1201 the men of Gloucester had to pay forty marks to recover the king’s good will, lost because they did not provide him with the lampreys he had ordered for his visit in late October.’In 1205, the king ordered Reginald of Cornhill to buy wine for him and send it to Nottingham, warning him to "know that if the wines are not good we will betake ourselves against you for it". Clearly 'John’s government seems to have expected, or even wanted, to arouse fear.’

The extent to which the government deployed violent and

aggressive methods actually led to confusion, as the king and his officials

struggled to keep track of whom they had attacked and why. In fact John seems to have encouraged a

policy of ‘disseise first and ask questions later’ in his officials, as when

‘he ordered Falkes de Bréauté to restore his wife’s inheritance to Roger Corbet, apparently a Gloucestershire landowner, but concluded by commending Falkes’s prudence "in that you disseised him and notified us of it".’

Although chroniclers decried John’s rule in general terms,

‘it is in the records of that government that the evidence for its activities... is mostly to be found. Those records are full of gaps, and in any case the personal character of John’s government means that many of its actions were not formally recorded. But despite these difficulties, which make quantification impossible, it seems likely that the level of demands and penalties, reinforced by threats, rose markedly in the later years of John’s reign.’

Henry’s commentary reveals, perhaps for the first time, not

only the sheer scale of John’s arbitrary treatment of his subjects but also its

routinisation. For this reason clause 39 was of fundamental importance, for it

‘aimed to subject intrusions of policy and personality to the constraints of due process. By doing so it proclaimed, and helped to install, regularity, routine and impartiality as qualities fundamental to the administration of justice, while in the longer term it set in motion developments which resulted in law ceasing to be no more than an agency of government.’