By the end of 1236, Henry was in desperate need of cash. His

marriage to Eleanor of Provence in January 1236 had been expensive and he had

promised £20,000 to Emperor Frederick II as the marriage portion of his sister,

Isabel. In line with clause 12 and clause 14 of Magna Carta 1215, the only way to

secure a tax was by the consent of his prelates and magnates. Accordingly,

Henry fixed a date of January 1237 for an assembly (or, rather, a ‘parliament’,

for this was the first meeting described as such in official records).

According to the St Albans chronicler Matthew Paris, ‘an

infinite multitude of nobles’ attended the parliament, which took place at the

palace of Westminster. When they were all seated, William Ralegh (the king’s

most senior judge) rose and, ‘as if a mediator between the king and the

magnates of the kingdom’, set out Henry’s request. As with other taxes of this

period, the king didn't have a specific sum in mind but a proportion (that is, a proportion of the value of people’s moveable goods). The sum requested was a thirtieth.

The king’s demand was met with an angry response from bishops

and barons. They complained ‘indignantly’ about the various taxes they had been

made to pay in recent years, as well as Henry’s neglect of their interests. Disturbed

by this outburst, Henry promised that in future he would abide by the counsel

of his native magnates. He fervently denied rumours of any attempt to procure

an annulment of Magna Carta from the pope and promised, there and then, to

observe the Charter.

Henry did acknowledge, though, that his behaviour over the

previous few years had not been spotless. In fact, his tendency to listen to

bad counsel might well have caused him to fall under the general sentence of

excommunication that had been pronounced in 1225 by the then archbishop of

Canterbury, Stephen Langton, against all who violated Magna Carta. Accordingly,

Henry arranged for the sentence to be renewed by the current archbishop, Edmund

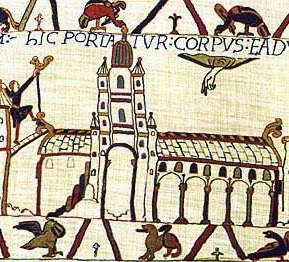

of Abingdon. This was done in a solemn ritual held in St. Katherine’s chapel in

Westminster abbey (this was the old building, founded by Edward the Confessor -

Henry didn’t start work on his new abbey until 1245). The king stood with his

right hand on the Gospels and his left hand clutching a lighted candle and swore

to observe Magna Carta from that day onwards. The archbishop and prelates proclaimed

‘Let it be done’ and threw down their own candles to extinguish them. This caused

a great amount of smoke and an unpleasant smell that irritated the eyes and nostrils

of the audience. The archbishop, though, recognised this as a teachable moment

and declared: ‘Thus let the condemned souls of those who violate the Charter,

or who interpret it improperly, be extinguished, and let them likewise smoke

and stink.’

Henry was to confirm the 1225 issue of Magna Carta again in

1253 and 1265, both times enforced by a sentence of excommunication.

No comments:

Post a Comment